Which metalworking company wants wet chips that result in dirty work areas and container storage areas and cause a lot of effort for chip disposal with a lot of forklift traffic. They also result in the discharge of a lot of cooling lubricant and low scrap proceeds. The solution: Separate the metal chips from the cooling lubricant. The question remains: how? Briquetting and centrifuging are the primary processes used for this. But what are the respective requirements, challenges and advantages of the two options? What are the costs?

BY PETER KLINGAUF

Ruf Maschinenbau, Zaisertshofen, addressed these questions in a whitepaper. In it, the developer and manufacturer of innovative briquetting systems for wood, metal and other residual materials goes into detail about the advantages and weaknesses of both processes, so that interested parties can get a good overview (Fig. 1). This technical article summarises the most important points.

How do centrifuges and briquetting systems work? Metal swarf in any form is a valuable raw material that needs to be utilised in one way or another. During centrifuging, the chips are subjected to high centrifugal forces in a rotating drum, which results in the separation of chips and cooling lubricant (cooling lubricant - i.e. oil or emulsion). A distinction is made between continuous, moving floor and batch centrifuges. The first two are automated systems in which either the material at the edge of the bowl is pushed upwards by continuously following chips or the material is discharged by lifting movements of the base. Batch centrifuges are usually fed with chips manually.

During briquetting, the chips are compacted by pressing. Fully automatic, hydraulic briquetting presses are mainly used for this in the metal sector (Fig. 2).

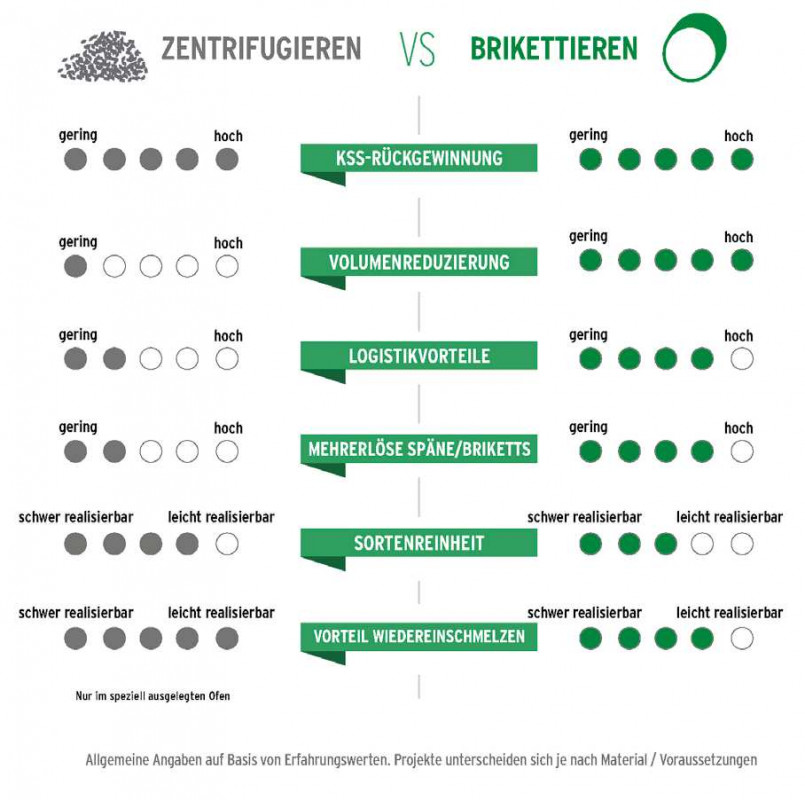

The effect: The volume is significantly reduced - the value for aluminium is typically 1:10 - and the coolant (oil or emulsion) escapes. The user receives a compact, dense chip briquette as well as the recovered cooling lubricant, which can be fed back into the production process, which is particularly lucrative for cutting oils. The quantity of cooling lubricants recovered during briquetting corresponds approximately to that of automated quality centrifuges. Manual batch centrifuges only achieve lower degrees of dewatering (Fig. 3).

Additional revenue from chip marketing

In addition to the recovery of the coolant, the reliable, reduced residual moisture of the centrifuged chips or briquettes is another important advantage of chip treatment. This ensures a defined scrap quality, which saves tiresome discussions with the customer about the water content.

The usual residual moisture content is between two and six percent for aluminium briquettes and between two and four percent for steel briquettes. Push floor centrifuges and briquetting presses with very high pressing force tend to achieve lower values, in some cases even lower (depending on the quality of the chips).

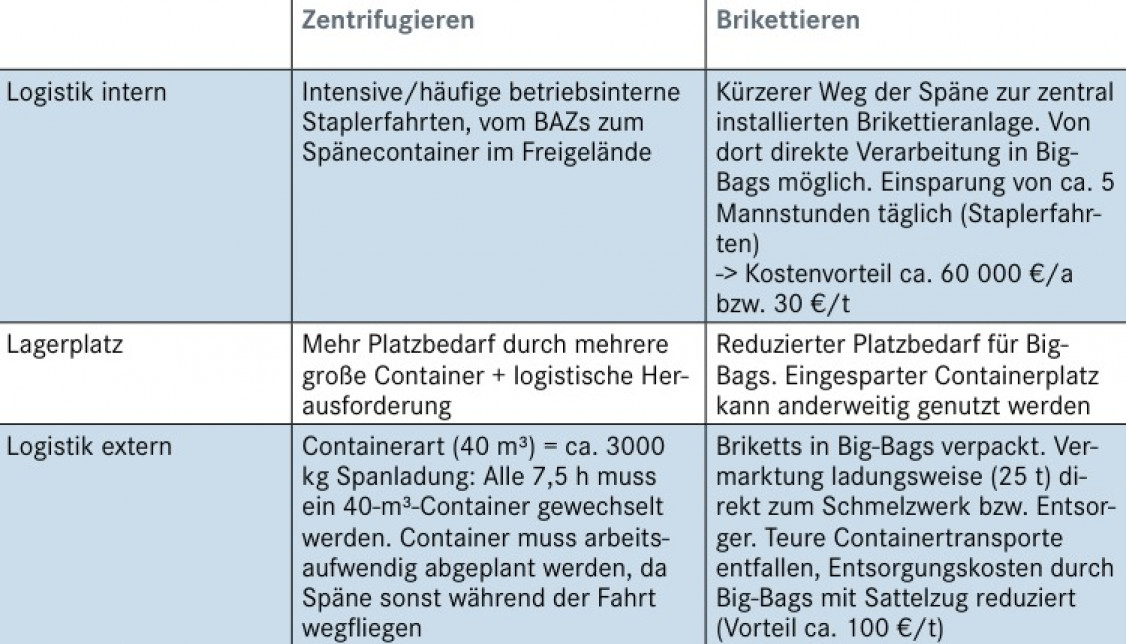

However, the briquettes produced by pressing have further advantages. Compared to the dry chips produced during centrifuging, briquettes are also characterised by a reduction in volume. They can be handled like general cargo and transported cost-effectively, even in full loads. This eliminates the need for expensive container transport via skip loaders or roll-off tippers, for example.

An additional advantage is that producers can use briquettes to contact specialised wholesalers or smelting plants, even if they are further away. This means that recycling routes can be optimised and trade chains shortened - which increases recycling revenues. This is particularly noticeable in the case of unmixed aluminium briquettes. It is not uncommon for high double or even triple-digit euro amounts per tonne to be achieved as additional revenue. This means that in many cases, the investment in a briquetting system pays for itself in just one or two years.

However, it is not possible to make a generalised statement about the additional revenue from briquettes compared to chips. This is because it depends on various factors: the quantity of chips or briquettes, the current market prices, the purity and alloy of the scrap, the respective defined scrap quality and the savings during transport.

Briquetting has a further advantage when treating grinding sludge. This is because centrifuging the fine grinding chips can cause sparks to form, posing a fire hazard depending on the material. This risk does not exist with briquetting. After all, the potential reactive surface of the chips is extremely reduced by the compaction. Also important: Briquetting eliminates the dust nuisance, which contributes to improved occupational safety and environmental protection.

There are only two cases where briquetting is not directly recommended. Firstly, if there are mixtures of chips with non-ferrous and ferrous metals. This rules out high-quality marketing of the briquettes. Secondly, there are a few very specialised melting processes that rely on loose chips.

What do the systems cost?

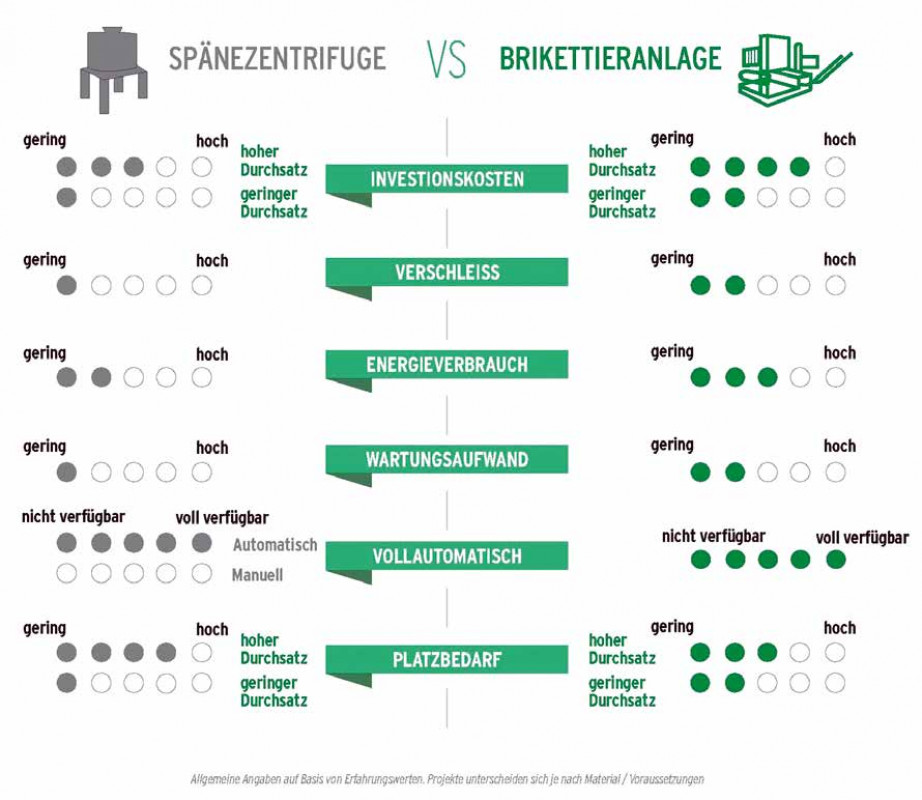

The investment volume of a chip processing system depends largely on the required throughput, the desired degree of automation and the necessary peripheral equipment of the system. For this reason, the procurement costs for centrifuges and briquetting systems can only be compared if the exact requirements are known. Table 1 shows the comparison using a project example.

In addition to the initial investment, the running costs (per tonne of chips) must also be included in an assessment. These are power requirements, operating and maintenance times as well as maintenance costs. Centrifuges generally have a lower power consumption, but usually run continuously, while presses are only in operation when chips are fed into them. The time required for maintenance and operation is very low for both systems. Centrifuges and briquetting systems also have similar maintenance costs: the chip centrifuge requires an annual UVV inspection, which must be carried out every three years in dismantled condition. In addition to the downtime of the system, the inspection itself causes further costs. On the other hand, the briquetting system incurs the expense of replacing hydraulic hoses, seals, hydraulic oil and filters.

Before making a purchase decision, the total costs should always be compared with the resulting benefits. In addition to the reuse of the cooling lubricant, the additional revenue from the briquettes and the overall logistical benefits also have an impact. Qualified advice from experts such as those employed by RUF Maschinenbau is indispensable. They are happy to make their extensive expertise in chip handling available in order to design a customised briquetting system depending on the material, the required throughput and the production conditions. With more than 6000 briquetting presses sold in over 100 countries, RUF is the world market leader for hydraulic briquetting machines. For example, the smallest machine RUF Formica with a motor output of 2.2 kW can achieve a throughput of up to 100 kg/h (depending on material and chip type). The largest machine (RUF 90) with 90 kW achieves up to 2500 kg/h for aluminium, up to 3000 kg/h for cast iron and up to 5000 kg/h for copper materials.

Checklist for the procurement process

Metal swarf as a valuable raw material (Fig. 4): Before investing in a chip treatment system, it is important to thoroughly examine the potential it offers. Factors such as coolant recovery, volume reduction, reduction of logistics costs (internal & external) and space requirements, additional scrap yields and production conditions have a major influence on the cost-benefit ratio. It is therefore worth making a decision based on the following questions:

- What is the budget? What level of automation is required and what labour costs are acceptable?

- What quantities of chips and how many types are to be processed? Will they be disposed of together?

- Is decentralised or centralised treatment of the chips planned?

- How much space is available in production or on site?

- Should space be saved for chip containers and/or chip gates? Should lubricoolant drip losses be eliminated and environmental hazards prevented at the same time?

- Should forklift traffic and lorry journeys be reduced?

- Is the residual moisture content of the chips or briquettes at the recycler or in the melting process an issue? What maximum residual moisture content is acceptable after treatment? In the case of melting plants: Is the melting process suitable for loose chips and briquettes or not?

- Does the disposal company accept briquettes? If so, how much more does he pay for them compared to chips? Can alternative customers be requested?